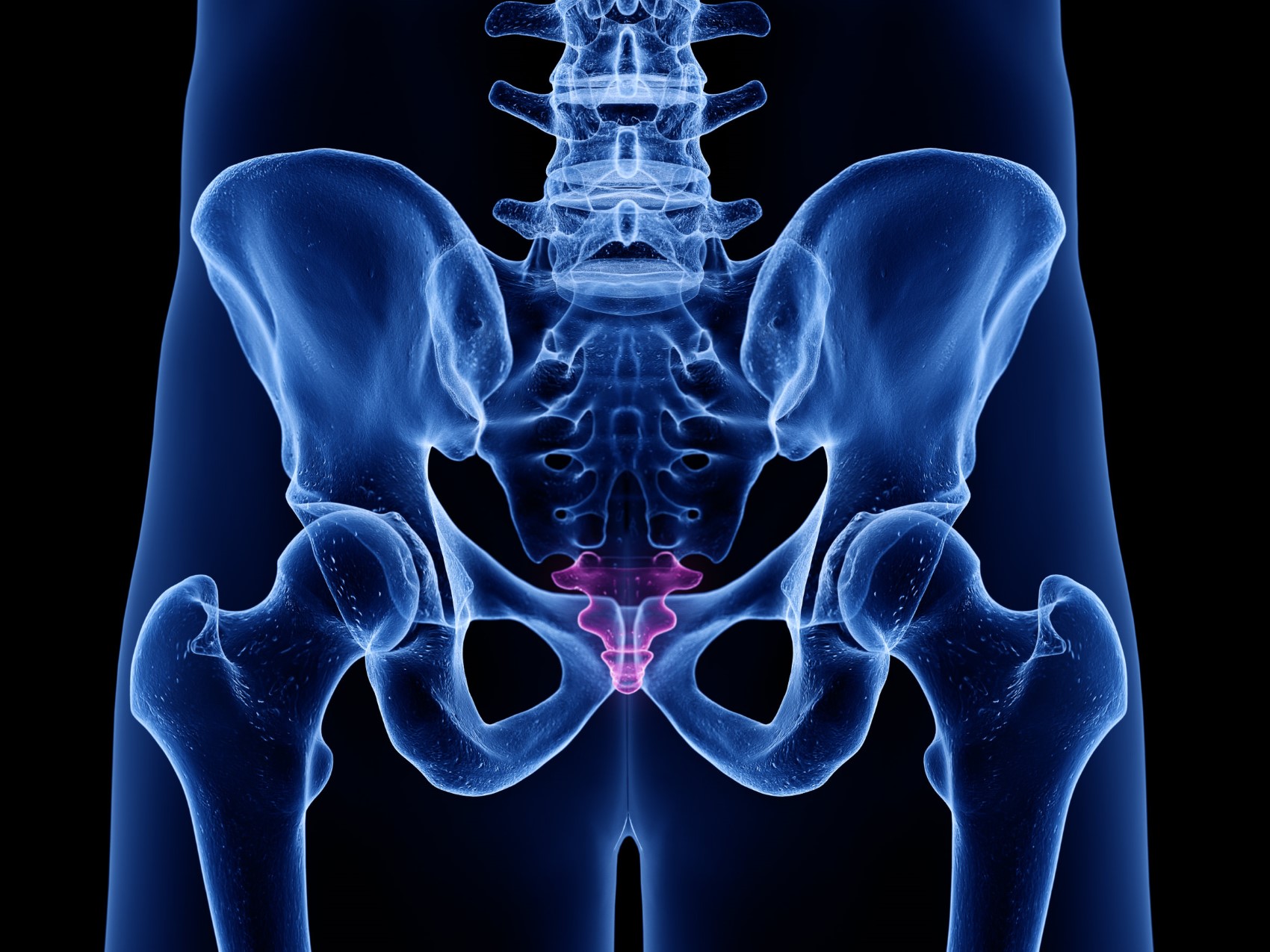

Coccydynia (AKA Tailbone Pain): What Causes it? How Do I Get better?

Tailbone pain, also called coccydynia or coccygodynia, is pain associated with the coccyx – the small triangular shaped bone at the bottom of the spinal column just below the sacrum. The coccyx is typically composed of three to five fused (or semi-fused) bony segments and connects to the sacrum via the sacrococcygeal joint. The coccyx serves an important role as the attachment site for multiple muscles, ligaments, and tendons that support the pelvic floor and provide weight distribution, stability, and balance when sitting.1 The nerves of the coccyx include the somatic nerves, which carry pain and other sensations to the brain. Additionally, the ganglion impar, a cluster of sympathetic nerve fibers located in close proximity to the sacrococcygeal joint, appears to be involved in various forms of sympathetically maintained pain in the pelvic region including coccydynia.1

Risk Factors and Causes

Although the exact prevalence of coccydynia is unknown, tailbone pain is often encountered in the clinical setting and can be debilitating when severe. Risk factors for developing coccydynia include female sex and obesity. Coccydynia is five times more common in females than in males.2 Elevated body mass index associated with obesity may affect how a person sits and the proportion of weight placed on the coccyx.3,4

The most common cause of coccydynia is direct external trauma to the tailbone. This can occur from a fall onto the buttocks causing the coccyx to be bruised, broken, or dislocated.5 Repetitive minor trauma, such as prolonged sitting with poor posture or sitting on hard or unsupportive surfaces can also increase the risk of developing tailbone pain. In addition, internal trauma associated with childbirth is another cause of coccydynia. Abnormal sacrococcygeal joint movement (both hyper- and hypomobility), osteoarthritis, and bone spurs can all result in coccygeal pain.5,6 Other rare but serious causes of tailbone pain include infection and malignancy of the coccyx itself or surrounding tissues.

Symptoms

Tailbone pain can vary from a dull ache to an intense stabbing pain. Coccydynia pain is typically well localized to the tailbone and does not radiate into the legs or through the pelvis. Pain usually worsens with sitting or any activity that causes direct pressure over the bottom of the spine. Often pain is worse when sitting on hard surfaces and with leaning back while in a seated position which places even more pressure directly over the coccyx.7 Transitional movements, such as moving from a seated to standing position can also be painful and may indicate dynamic sacrococcygeal instability. Pain may also worsen with bowel movements or during sexual intercourse.

Diagnosis

Physical Exam:

A focused external examination of the coccyx should be performed inspecting for any rash, discharge, or fistula (abnormal opening) which could suggest an underlying infection or cyst. Pain should be reproduced with focal external palpation of the posterior aspect of the coccyx. Careful palpation of the adjacent structures, such as the para-coccygeal muscles and ligaments, and ischial regions can help evaluate for other causes of tailbone pain. Notably, digital rectal examination allows for palpation of the anterior coccyx and may be helpful in evaluating the degree of coccygeal mobility.

Imaging:

An x-ray of the coccyx is typically the initial image of choice as it can evaluate for fracture, malalignment/dislocation, and joint degeneration (i.e. osteoarthritis). X-rays can also be obtained in standing and sitting views to evaluate for dynamic sacrococcygeal instability. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be considered when x-rays are normal, pain persists, and/or in cases where infection, malignancy, or other soft tissue abnormalities are of concern.8

Treatment

There are a number of conservative treatment options available for coccydynia. Encouragingly, the vast majority (90%) of patients respond favorably to conservative care.5 However, for patients who continue to experience persistent pain despite conservative measures, there are additional treatments available.

Cushions – Wedge cushions, including the “Tush Cush” can help distribute weight away from the painful coccyx and make sitting more comfortable. These cushions have a cutout in the back to prevent direct pressure transfer onto the coccyx, and a wedge shape to promote forward trunk lean so that weight is mainly borne on the ischial tuberosities (sit bones) and posterior thighs, rather than the coccyx.

Ice and/or Heat – Ice applied topically to the affected area 20 minutes per session, three to five times per day, can be an effective anti-inflammatory and pain reducer. Heat may also be trialed per the patient’s preference, but appropriate caution to avoid burns is advised.

Medication – Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Advil), naproxen (Aleve), or selective COX-2 inhibitors can be helpful in the acute setting to decrease both pain and inflammation. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) can also help with acute pain control.

Physical Therapy – Pelvic floor physical therapy can be helpful for patients with painful adjacent para-coccygeal muscles and pelvic floor muscle spasm. Internal coccygeal manipulation may also provide pain relief. In addition, physical therapy can improve core strength and assess and improve sitting posture.

Injections – For patients with persistent pain despite conservative care, local anesthetic or local anesthetic plus glucocorticoid (steroid) injections can be considered. Injections, guided by fluoroscopy (live x-ray), are typically directed at the sacrococcygeal joint and the ganglion impar and have been shown to provide significant pain relief. 9,10 In one study of patients who failed to respond to conservative management strategies, ganglion impar anesthetic block successfully provided >50% pain relief in 82% of patients for a mean duration of six months.11 A recent systematic review of the available literature also found ganglion impar anesthetic blocks to be a successful means of pain control in coccydynia.12

Surgery – Finally, for intractable coccydynia, surgery to remove the coccyx (coccygectomy) is a last resort.

In Conclusion

While many cases resolve with little or no medical treatment, coccydynia can become chronic and may be associated with severe and disabling pain. Fortunately, there are a variety of treatment options available for pain relief. If you are experiencing tailbone pain, please call to schedule an appointment at Desert Spine and Sports Physicians so that our team of board-certified specialists in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) can help diagnose and treat your issue. We offer appointments and in-office procedures at all of our Phoenix, Scottsdale, and Mesa locations, and we look forward to helping decrease your pain and improve your function.

References

- Woon JT, Stringer MD. Clinical anatomy of the coccyx: A systematic review. Clin Anat. 2012 Mar;25(2):158-67. doi: 10.1002/ca.21216. Epub 2011 Jul 7. PMID: 21739475.

- Fogel GR, Cunningham PY 3rd, Esses SI. Coccygodynia: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004 Jan-Feb;12(1):49-54. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200401000-00007. PMID: 14753797.

- Patijn J, Janssen M, Hayek S, Mekhail N, Van Zundert J, van Kleef M. 14. Coccygodynia. Pain Pract. 2010 Nov-Dec;10(6):554-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00404.x. Epub 2010 Sep 6. PMID: 20825565.

- Maigne JY, Doursounian L, Chatellier G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000 Dec 1;25(23):3072-9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012010-00015. PMID: 11145819.

- Lirette LS, Chaiban G, Tolba R, Eissa H. Coccydynia: an overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. Ochsner J. 2014 Spring;14(1):84-7. PMID: 24688338; PMCID: PMC3963058.

- Patel R, Appannagari A, Whang PG. Coccydynia. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008 Dec;1(3-4):223-6. doi: 10.1007/s12178-008-9028-1. PMID: 19468909; PMCID: PMC2682410.

- Foye PM. Coccydynia: Tailbone Pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017 Aug;28(3):539-549. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2017.03.006. Epub 2017 May 27. PMID: 28676363.

- Woon JT, Maigne JY, Perumal V, Stringer MD. Magnetic resonance imaging morphology and morphometry of the coccyx in coccydynia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 Nov 1;38(23):E1437-45. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a45e07. PMID: 23917643.

- Mitra R, Cheung L, Perry P. Efficacy of fluoroscopically guided steroid injections in the management of coccydynia. Pain Physician. 2007 Nov;10(6):775-8. PMID: 17987101.

- Sagir O, Demir HF, Ugun F, Atik B. Retrospective evaluation of pain in patients with coccydynia who underwent impar ganglion block. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020 May 11;20(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12871-020-01034-6. PMID: 32393277; PMCID: PMC7212553.

- Gunduz OH, Sencan S, Kenis-Coskun O. Pain Relief due to Transsacrococcygeal Ganglion Impar Block in Chronic Coccygodynia: A Pilot Study. Pain Med. 2015 Jul;16(7):1278-81. doi: 10.1111/pme.12752. Epub 2015 Mar 20. PMID: 25801345.

- Choudhary R, Kunal K, Kumar D, Nagaraju V, Verma S. Improvement in Pain Following Ganglion Impar Blocks and Radiofrequency Ablation in Coccygodynia Patients: A Systematic Review. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo). 2021 Oct 28;56(5):558-566. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1735829. PMID: 34733426; PMCID: PMC8558944.